|

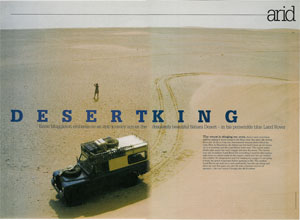

The sweat is stinging my eyes, there’s sand everywhere and I’m making it worse trying to rub them clear, fine gritty silt etching them raw. As far as I can see, in every direction, the monumental crescent dunes block the view. Here in Mauritania, the Saharan sun has barely been up two hours, is scorching, the Land Rover won’t start. The starter makes all the right noises but won’t engage and turn the motor. The twenty year old, ex-military Land Rover has everything I need for this journey, right down to the hand crank for the engine, which has me worked into a lather. It’s dripping hot and I’m wasting my energy, it’s not going to kick, the petrol evaporates before sparking to life. This was the very reason I bought this old leviathan, the modern are tech savvy and comfortable, but this was cheap and there are very few parts you can’t fix with a hammer and set of spanners.

Africa bound. The Sahara desert. Doesn’t matter how many times you cross or fail to cross this great desert, there’s an awe to this place that very few other deserts come close to. It’s not pretty, the few oasis are fly ridden stink holes, the only times you can sensibly cross, in winter, the days are baking hot, the nights freezing cold and the wind blows fine silty sand into every corner that matters. It’s skin chapping dry, there are minefields littered from east to west and bandits think nothing of stealing your ride. And these are all the reasons we want and need to cross. This is the last great driving challenge. This is the Sahara, and by God, when the dust is settled and you are home with a beer in your hand telling huge stories, is it sexy!

I’ve dreamt of this journey for years, and conveniently just pulled in a commission to film three tribes in Africa for National Geographic TV, and convinced myself the best way to do it would be to drive. Of course it wasn’t, much quicker and cheaper to fly, but that was besides the point.

The preparation is endless, mostly because I’d found the army driving range just next door in Wiltshire. Every opportunity I had I’d scream along the back country roads in search of ditches to see if I could crawl out of them. Little did I know that pastoral Wiltshire would hardly be preparation for driving in West Africa. A good day in Mali, the Land Rover rattles and is smashed about more in one afternoon than a year of abuse at home. Putting the vehicle through its’ paces before heading off pays dividends ten fold on a driving trip. Keeping the costs down at home doesn’t weigh up when something breaks down in the middle of nowhere. If it’s dodgy, replace it. That’s the beauty of these old Landrovers, there are plenty of parts and are great value for the money. I grabbed an ex army vehicle, it had all the pros I could think of, huge under-seat fuel bins holding 100 liters, an oil cooler in front of the radiator that worked brilliantly in the heat and had been well maintained for a twenty year old machine. On the down side, the suspension was rock hard, probably designed for carrying a platoon full of squaddies, and someone had painted it Periwinkle Blue. Terrific.

Periwinkle or not, it needed to do it’s job. One of those jobs was driving the motorways of France and Spain. It failed miserably, I spent a week driving, maxed out at 60 MPH downhill, with a hurricane up my tail. With no sound-proofing, and a gearbox sounding like a jumbo on take off I wedged ears plugs deep into my canals.

I wanted Africa, and didn’t hang about longer than I needed to in Europe. With a one tracked mind, even northern Morocco blurred past. Well as best it could at my deliriously slow speeds.

Thousand year old palm groves and the Medina’s of Marrakech behind and the peaks of the Atlas mountains ahead I cut every corner on the map I can. The range is harsh, rugged rock-strewn land, and freezing at night. But this is where this brute of a tractor does it’s best. Very little gets in it’s way and as I work to the roof of the divide I get the first taste of the Sahara. Up here the warm winds are welcoming, the sands have a distinct dusty scent, and the dunes reach as far as curves on the earth. I’m a kid in a sand box again, and I’m ready to play til’ my hearts content.

Due to spats across the sands and an ongoing border dispute, Morocco and Mauritania have a minefield plonked between them. The Moroccans are, however, diligent about the value of their tourist industry and realise they can’t have natty tourist blowing up on their southern border. Twice a week they provide a military convoy that guides you to the edges of the minefield and points you through it to the Mauritanian authorities over the next sand bank. If you wondered what ever happened to your neighbours’ stolen car and every overlander on route to southern Africa, the Moroccan army convoy, funnels them into the enormous sand pit of Mauritania.

Nouadibou, the first desert village in Mauritania sits on the edge of the dunes, bears no roads and a solitary train line coming in from the phosphate mines. Moor guides abound. The Arabs know the dunes like the back of their own hand, but at £150 a head, hustle a good trade to guide you south. They tell you of countless travellers lost in the fierce sand storms, the raging thirst when you can’t find the waterholes, and bandits that would slit your throat or shoot you for your possession. Laughing at their horror sales pitch I fill up and set off without one on a short cut from the village along the estuary where the tide is out. I’m twenty minutes across the estuary when I’m buried up to the doors in wet, slimy sand, and each move buries me deeper. I relive my conversation with the Moor guide. As the tide turns, a little panic rises. A truck full of Arabs crossing the desert sees my dilemma and help dig me out. They don’t smirk and grin as I would have done, the desert to them is too serious a place. There’s a bond between them and a duty to help out those in trouble.

I don’t turn round and pick up a guide but my little foray tempers my mood and I think more in earnest how to tackle the looming dunes ahead. Most of the desert is a hard flat piste where you can drive as fast as you want until you hit the wall of sand. There is no way around the dunes, they stretch from the east and wash into the Atlantic Ocean on the west.

Initially they are impossible to drive in, once stuck the only way out is to dig with shovels and lay sand ladders in front of the wheels to get moving again. Time behind the wheel never really makes it easier but subtle differences in the shades of colour indicate where the sand is less soft. Time to sit back and enjoy the desert is a luxury you don’t have, as the ever-dwindling supply of water and petrol niggles at the back of your mind. In Nouakchott, Mauritania’s capital south of the dunes, I swapped stories with travellers from the convoy and realised that the desert is a harsh place to hone your skills. A motorbike pillion broke her back when her boyfriend misjudged a dune, and a South African team playing in the sand sheared off all their engine bolts, stranded 250 miles from the nearest waterhole. And this was only during the week I crossed.

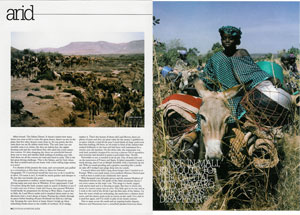

I wasn’t here just to cross the desert, but moreover to find my tribes. Crossing the Senegal river into black Africa feels like the lights have just been switched on. Senegal is teeming with life and song. Lush green is the new “it” colour, gone are the never ending shades of tan. After a night out in Dakar the urge to push deeper East into the continent is irresistible. Once in Mali, to the capital city Bamako, the roads disappear. The Land Rover becomes my battering ram. Smashing through tall grasses, forests, streams and trees struggling up and down gullies and through rav ines you never knew were there. The locals have no idea where the capital city is, they’ve never been there. The route follows the Bakoye river, a tributary of the Senegal, a 250 miles, six day trek from Kita to Bamako the capital proved inaccessible in anything other than a four wheel drive.

The Rover took a beating and soon its weaknesses were exposed. The roof rack had snapped along three joints, and clattered up top leaving me with the lingering feeling that I was still back in the night clubs of Dakar. The steering ball joints are completely shot, the carburettor sick, and the body work looks like the village fait had pummelled it with sledge hammers. Rolling into Ghana, seven thousand miles and three months from setting off, to the world’s friendliest people and the cheapest Land Rover parts anywhere was Christmas come early. The trouble I still hadn’t found the first tribe I was to film. The journey so far had taken me a month longer than I thought it would. I needed to be deep in the heart of the Congo Basin to film the hunting skills and lifestyle of the Pygmies. Between us was six more countries, thousands of miles, endless corruption and the worse infrastructure in Africa. I did find them. This section was an epic in itself. The Periwinkle blue Land Rover however turned into a shadow of it’s former self, a dog eared, battle scarred victim of Africa. I didn’t fare much better, twice ravaged by malaria, weakened by the long, hard days digging the vehicle through the mud’s of the Congo. I eventually found the Pygmies, and during my first hunt, found out the hard way that at six foot three, genetics was against me in the dense rainforest.

If at the back of your head this trip’s on your mind, go buy a ridiculously old, cheap Land Rover, give your self a few weekends to Wales and back, add all the toys, then pick a date. Do yourselves a favour, don’t pick summer.

|